At 75 years old, Ben and Yolanda don’t need the money that they’re forced to take out of Ben’s IRA to satisfy his Required Minimum Distribution (RMD). And they worry that the constantly increasing distributions will push them into higher brackets and trigger Medicare IRMAA surcharges. Here’s what they can do differently to help minimize the impact of their RMDs.

At 75 years old, Ben and Yolanda don’t need the money that they’re forced to take out of Ben’s IRA to satisfy his Required Minimum Distribution (RMD). And they worry that the constantly increasing distributions will push them into higher brackets and trigger Medicare IRMAA surcharges. Here’s what they can do differently to help minimize the impact of their RMDs.

Direct Charitable Giving

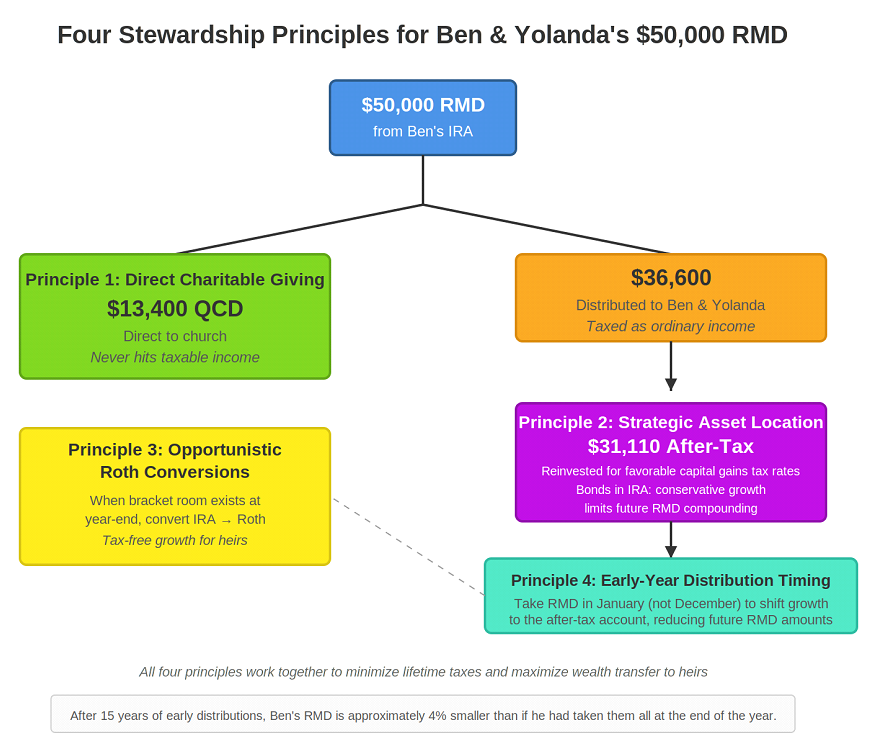

First, the money they give to charity, including their church tithing, can come directly from the IRA using Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs). Any amount up to $105,000 per year (as of 2026) can be distributed to qualified charities, and that amount applies to satisfying the RMD. Ben and Yolanda tithe $700 monthly and decide to add 10% of this year’s $50,000 RMD, bringing the total to $13,400. This money gets sent directly to their church and it never appears as taxable income.

Strategic Asset Location

But they still have $36,600 that must hit their taxable income this year. They want to preserve as much of their money as possible for their kids and of course if they need it for their personal care later in life. So, the money gets reinvested in a taxable non-retirement (or after-tax) account which is invested with the same long-run mindset as they have in the IRA, but with a coordinated investment objective. Overall, they want to maintain a traditional Growth with Income, or a 60/40 mix of 60% stocks to 40% bonds.

They have $1,230,000 in the IRA and $410,000 in the after-tax account, for a total of $1,640,000. To meet their investment objective, 60% or $984,000 should be invested in stocks, while the remaining $656,000 is invested in fixed income (bonds).

It is important to know that any money that comes out of the IRA is taxed as ordinary income. It gets charged the highest tax rate. To the extent possible, Ben and Yolanda use the IRA to hold the bulk of their most conservative investments, the bonds. Conservative investments have less risk and therefore they tend to grow slower, helping mitigate the future size of their unneeded RMD.

Stock owners participate in corporate earnings in two ways: dividends or appreciation. Many (if not most) dividends are taxed as long-term capital gains (LTCG), and those tax rates are always lower than a taxpayer’s marginal income tax bracket. In fact, the LTCG rate is set by the marginal income tax bracket. And they are ZERO for people in the 12% or lower tax bracket (some limits apply).

Appreciation is always considered a capital gain, but it doesn’t get taxed until the investment is sold, or “realized”. And in turbulent times, an investment can be sold at a loss, called tax-loss harvesting, to offset realized gains. The rules around this technique are beyond the scope of this story so I buried them in a footnote. The important point is that in a after-tax account, the owner has some control over when they trigger capital gains taxes. But to the heirs, the investments in the after-tax account can be immediately sold with almost no taxation, because beneficiaries get a “step-up in basis.” To them, it’s as if they just bought the investments on the day the last parent died, so the only gains are what occurs after their passing.

Opportunistic Roth Conversions

Ben and Yolanda want their heirs to receive as much as possible, with as little taxation or difficulty to their financial lives as is possible. The money in the IRA is the biggest problem for the heirs, because under current law they must remove all the money and trigger the ordinary income tax within ten years.

That’s why they started doing Roth Conversions before the RMD muddied the picture for them. In prior years, they utilized Roth IRA Conversions to shift money from the IRA into an account even more tax-favorable than the after-tax account. They will review the idea at the end of the year when they know if there will be any room for additional income in their 12% Federal Income Tax bracket. Because they opened that account five years ago, money coming out of it is never taxed. They give it a more aggressive investment objective and don’t factor it into their overall investment objective.

Early-year Distribution Timing

After Ben and Yolanda do the QCD, take the RMD and withhold the taxes, the IRA balance drops to $1,180,000 while the after-tax account sees an increase of $31,110 ($36,600 less 12% Federal and 3% State income taxes) to $441,110.

Last year, Ben waited until the end of the year to make these transactions, but he realized that his IRA grew substantially and the RMD almost pushed him into the 22% tax bracket. That would mean the realized capital gains inside the mutual funds in his after-tax account would get taxed 15%.

He dodged a bullet on that one!

And he learned firsthand about timing of the RMDs (and QCDs). This year, he’s taking the $50,000 out of the IRA as soon as possible in the year, so that those funds are working in the account where he can exercise some control over the taxable events. Additionally, the growth on those funds will not contribute to compounding the size of his RMD in the future.

We’ve done some modeling of the difference a beginning versus an end of year RMD can have on the lifetime balance of the portfolio. It seems like nothing in the first year, but it compounds and after a decade or more it can add up to six figures difference in the balance on which the RMD is calculated.

“Time in the market” is a catch-phrase used to get invested and to discourage market timing. Ben and Yolanda are working both sides of the concept. Getting money out of the IRA and into the tax-favored account as soon as possible, shifting an annual amount of growth from one to the other.

Summary

Tax arbitrage strategies like these can be complex. Every household is unique. Some tax thresholds, like tax-free Social Security, have phase-out ranges while others, like capital gains taxes and IRMAA surcharges, have steps. One dollar too much and you pay the higher rates.

Ben & Yolanda use four strategies to align their legal obligation to remove money from their traditional IRA (the RMD) with their goals of generous giving and reducing family tax burdens for two generations.

At Enduring Wealth Advisors® we use the latest software available to model our client’s tax situation as part of our ongoing service to them. Contact us now to arrange a review of your situation. We can help you avoid future potholes in your retirement investment strategy.

Footnotes

Tax-loss harvesting involves selling an investment at a loss to offset capital gains elsewhere in your portfolio. The IRS “wash sale rule” prohibits you from claiming the loss if you buy a “substantially identical” security within 30 days before or after the sale. To harvest losses while maintaining market exposure, investors typically sell one fund and immediately purchase a similar (but not identical) fund – for example, selling a total market index fund and buying an S&P 500 index fund, or vice versa. Losses can offset gains dollar-for-dollar; any excess losses up to $3,000 annually can offset ordinary income, with remaining losses carried forward to future years.

2 Assuming 5% annual growth (consistent with a bond-heavy IRA), taking the $50,000 RMD in January versus December creates a modest $2,500 balance difference after year one. But this compounds: after 10 years their IRA balance would be $30,000 lower with early distributions, and after 15 years it would be $47,000 lower—reducing Ben’s age-89 RMD by approximately $3,400.

Important Disclosures

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. Tax laws are subject to change and may vary based on circumstances. Consult with your tax advisor regarding your specific situation.

Research and development of this article included the use of artificial intelligence tools.

This is a hypothetical situation based on real life examples. Names and circumstances have been changed. The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. To determine which investments or strategies may be appropriate for you, consult your advisor prior to investing.

A Roth IRA conversion—sometimes called a backdoor Roth strategy—is a way to contribute to a Roth IRA when income exceeds standard limits. The converted amount is treated as taxable income and may affect your tax bracket. Federal, state, and local taxes may apply. If you’re required to take a minimum distribution in the year of conversion, it must be completed before converting.

To qualify for tax-free withdrawals, you must generally be age 59½ and hold the converted funds in the Roth IRA for at least five years. Each conversion has its own five-year period, and early withdrawals may be subject to a 10% penalty unless an exception applies. Income limits still apply for future direct Roth IRA contributions.